Rewiring Survival: Understanding Trauma’s Impact on Brain, Body, and Beyond

Imagine Sarah, a devoted mother, driving home from work one rainy evening. As she slows at an intersection, a speeding car skids through the red light and slams into her vehicle. In an instant, metal crumples and glass shatters. Though Sarah escapes with minor physical injuries, she finds herself reliving the screech of tires, the impact, the terror—long after her body has healed.

This visceral replay is trauma at work: a physiological cascade coupled with psychological imprints that persist beyond the event itself. Physiologically, trauma triggers the body’s ancient alarm systems—flooding the bloodstream with stress hormones, altering neural circuits, and even leaving epigenetic marks that can echo across generations. Psychologically, trauma can fracture our sense of safety, distort memories, and reshape emotions and relationships.

In this article, we’ll explore how trauma affects both brain and body, diving into the science behind stress responses, neural rewiring, and the emotional aftermath. More importantly, we’ll highlight actionable, evidence-based pathways toward healing—because understanding is the first step in reclaiming well-being.

Physiological Mechanisms of Trauma

The Body’s Alarm: HPA Axis Activation

When a sudden threat appears—whether a screeching car, a harsh word in childhood, or the flash of weapons in combat—the body’s ancient alarm system instantly revs into life. At its core lies the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, a three-way relay connecting the brain to the adrenal glands. The hypothalamus, sensing danger, secretes corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH). CRH travels a hair’s breadth to the pituitary, which then dispatches adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) through the bloodstream. ACTH’s final destination is the adrenal cortex, where it triggers a surge of cortisol—the body’s primary stress chemical.

Sympathetic Surge and Sleep Disruption

Cortisol mobilizes glucose for muscles, sharpens perception, and momentarily suppresses nonessential functions like digestion and immunity. Meanwhile, the autonomic nervous system shifts fully into sympathetic (“fight-or-flight”) mode: heart rate accelerates, lungs draw in extra oxygen, and senses become hyper-attuned. Under normal circumstances, once danger passes, parasympathetic signals restore calm. But in trauma—especially when danger is prolonged or repeated—this reset mechanism falters. Cortisol remains elevated even at night, sleep becomes shallow, and nightmares transform the bedroom into another battleground. Rather than restorative slow-wave sleep, individuals endure fragmented cycles and repeated micro-awakenings. Ironically, the very state designed for rest becomes a trigger—each half-wakened moment can reignite the HPA axis, perpetuating hyperarousal.

Neural Remodelling: Amygdala, Hippocampus, Prefrontal Cortex

Beyond this hormonal whirlwind, trauma reshapes key brain regions. The amygdala—the almond-shaped “sentinel” that tags sensory input as safe or threatening—grows hyper-reactive, prone to false alarms at the slightest cue: a backfiring engine or a raised voice. The hippocampus, our contextual memory hub, suffers cortisol-induced shrinkage, so memories of the traumatic event lodge as disconnected fragments rather than coherent narratives. Without a fully functional hippocampus to say, “You are safe now—this was then,” the mind can’t properly archive the experience. At the same time, the prefrontal cortex—our executive centre responsible for planning, decision-making, and regulating emotion—loses some of its regulatory influence over the amygdala, making it harder to soothe fear once it erupts.

Systemic Ripples: Inflammation, Metabolism, Digestion

These local changes ripple outward into systemic consequences. Chronically elevated cortisol dysregulates immune cells, increasing inflammation that can fuel everything from cardiovascular disease to autoimmune flare-ups. Metabolic processes go awry, contributing to weight gain and insulin resistance. Gastrointestinal distress is common, as the body perpetually diverts energy away from digestion. In essence, trauma reframes the entire organism as if under siege—even when the original threat is long gone.

Epigenetic Echoes: Intergenerational Transmission

Remarkably, the echoes of trauma may extend across generations. Researchers studying survivors of extreme adversity—from Holocaust survivors to war-torn refugee families—have documented altered DNA methylation patterns on genes that regulate stress responses. These epigenetic markers do not change the underlying genetic code but adjust how readily stress-related genes are expressed, which we will explore next. Children and even grandchildren of trauma survivors can inherit a biological propensity toward heightened HPA-axis reactivity, making them more vulnerable to anxiety and hyperarousal. In this way, trauma can leave molecular “scars” on the tapestry of family biology, underlining the urgency of early intervention and resilience-building.

Cortisol Rhythms: Trauma vs. Typical Profile

Finally, when we chart cortisol levels across a 24-hour day, a stark contrast emerges between trauma-affected and non-traumatized individuals. In someone without PTSD, cortisol peaks shortly after waking—fuelling morning alertness—and gradually tapers toward evening, allowing for restful sleep. In trauma survivors, however, the curve flattens or even inverts: elevated evening cortisol undermines sleep, while the morning surge may be blunted or delayed, leaving individuals fatigued by day and wired by night.

By understanding how the HPA axis, central nervous system structures, sleep architecture, whole-body systems, and even our epigenome are interwoven in the tapestry of trauma, we can better target interventions—restoring balance not only in the brain but throughout the body.

Psychological Dynamics of Trauma

Understanding PTSD, Complex PTSD, and Acute Stress Reaction

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) arises when, after exposure to a traumatic event—such as assault, accident, or combat—the brain’s normal recovery processes stall. Rather than integrating the memory and returning to baseline, the individual remains locked in hyperarousal, re-experiencing, avoidance, and negative mood states for more than one month, with significant impairment in daily life.

Complex PTSD (C-PTSD), recognized in ICD-11, develops after prolonged, repeated trauma—often interpersonal (e.g., childhood abuse, domestic violence). In addition to core PTSD symptoms, C-PTSD features persistent disturbances in self-organization: severe difficulties in emotion regulation, a chronically negative self-concept (“I am worthless”), and relational impairments (difficulty trusting or sustaining relationships).

By contrast, ICD-11’s “Acute Stress Reaction” (also called Acute Traumatic Stress) describes stress responses in the first days to weeks post-trauma. Symptoms may mirror PTSD—intrusive thoughts, hypervigilance, dissociation—but they resolve within one month. If these symptoms persist beyond four weeks, a diagnosis of PTSD or C-PTSD is considered.

Cognitive, Emotional & Social Ripple Effects

Trauma doesn’t just alter internal experiences; it reshapes how individuals interpret and engage with the world. Cognitive distortions—such as overgeneralized beliefs (“No place is safe”)—can lead to social withdrawal. Emotionally, survivors oscillate between emotional numbing and sudden outbursts of anger or fear.

Sociologically, these shifts can cause misunderstandings: a colleague’s well-meaning feedback may be perceived as criticism, triggering defensive withdrawal. Friendships can fray when survivors decline invitations, not from disinterest but from overwhelming anxiety. Children of trauma survivors may misinterpret parental hypervigilance as hostility, affecting family cohesion and potentially perpetuating cycles of mistrust.

Example: Maria, who survived childhood neglect, finds group meetings triggering; she often arrives late or leaves early. Her peers see this as rudeness. Once she explains her need for controlled entry and exit, the group adapts—adding “quiet breaks”—which improves both her participation and overall group empathy.

Coping Mechanisms: From Maladaptive to Adaptive

Many natural coping strategies become maladaptive when over-relied upon:

Dissociation can fragment attention and memory, impairing work or study. To transform this, survivors can practice grounding techniques—such as naming five objects in the room—to re-anchor in the present.

Substance use numbs distress but risks dependency. An adaptive shift might involve structured social support (peer groups, therapy) combined with healthy substitutes like art or music to process emotions.

Overcontrol (rigid routines) may collapse under minor change. Replacing this with flexible planning—building small “variability windows” into the day—can restore a sense of safety through mastery rather than rigidity.

By consciously identifying a maladaptive habit, naming its payoff (e.g., “Alcohol helps me sleep”), and then experimenting with healthier alternatives that meet the same need (e.g., herbal tea ritual, guided relaxation), individuals can gradually rewire coping patterns.

Post-Traumatic Growth: From Surviving to Thriving

Post-Traumatic Growth (PTG) describes positive psychological change following struggle with trauma. Growth often unfolds in areas of personal strength, relationships, appreciation of life, new possibilities, and spiritual development.

Anecdote: After surviving a near-fatal car crash, David found himself paralyzed by fear when driving. Through therapy, he not only reclaimed the road but later volunteered as a driving coach for other survivors. His narrative shifted from “I was nearly destroyed” to “I rediscovered purpose in helping others regain freedom.” Over time, David reported deeper empathy, stronger social bonds, and a renewed sense of mission—hallmarks of PTG.

Neurobiologically, PTG may reflect strengthened connectivity between the prefrontal cortex (regulation) and amygdala (emotion), enabling individuals to reappraise threats and integrate traumatic memories into a coherent life story. Psychologically, deliberate reflection—through journaling or guided narrative therapy—helps survivors construct meaning, transforming trauma from an endpoint into a springboard for growth.

By distinguishing PTSD, C-PTSD, and acute stress reactions, exploring the wider social fallout of trauma, mapping pathways from maladaptive to adaptive coping, and illustrating the journey of Post-Traumatic Growth, we gain a richer, more actionable understanding of trauma’s psychological landscape. This depth equips both survivors and supporters to navigate the road from survival toward genuine thriving.

In-Depth on Evidence-Based Therapies

Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (TF-CBT)

TF-CBT combines cognitive restructuring with gradual, supported exposure to traumatic memories. In early sessions, a therapist helps you build safety skills—like grounding and relaxation—before gently guiding you to revisit distressing memories in a structured way. Over time, you learn to identify “stuck” beliefs (e.g. “I am powerless”) and replace them with balanced appraisals (“I survived, and I have strengths to draw on”). Homework assignments—such as writing a trauma narrative—reinforce new perspectives and coping tools between sessions.Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR)

EMDR leverages bilateral stimulation—typically guided lateral eye movements or gentle taps—to help the brain reprocess traumatic images and emotions. While you hold a specific distressing memory in mind, the therapist directs your eyes back and forth. This dual attention appears to unlock the brain’s natural healing processes, enabling the memory to integrate adaptively rather than remain frozen in a high-arousal state. Clients often report that the vividness and emotional charge of traumatic memories decrease markedly over a series of eight to twelve sessions.Somatic Experiencing

Somatic Experiencing (SE) focuses on bodily sensations (“interoception”) rather than only on thoughts. Under a trained practitioner’s guidance, you track where you feel tension, tightness, or numbness. Through gentle titration—alternating between sensing and releasing small amounts of stored arousal—you gradually renegotiate physical responses to trauma. Over time, SE can restore a more flexible autonomic balance, helping you shift out of chronic fight-flight or shutdown modes.MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy

In controlled clinical settings, a few sessions of MDMA combined with psychotherapy have produced large reductions in PTSD symptoms. MDMA’s prosocial and fear-reducing effects allow clients to revisit traumatic material with greater openness and less defensiveness. After the drug experience, integrative therapy helps weave new insights into lasting psychological change. Phase 3 trials suggest two to three MDMA-assisted sessions can yield benefits that endure for at least a year.Non-invasive Brain Stimulation (tDCS, TMS)

Techniques like transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) target the prefrontal cortex to enhance regulatory control over hyperactive limbic regions. Administered alongside psychotherapy, these approaches can accelerate reductions in hyperarousal and improve emotional regulation—especially for individuals who have not responded fully to talk therapy alone.

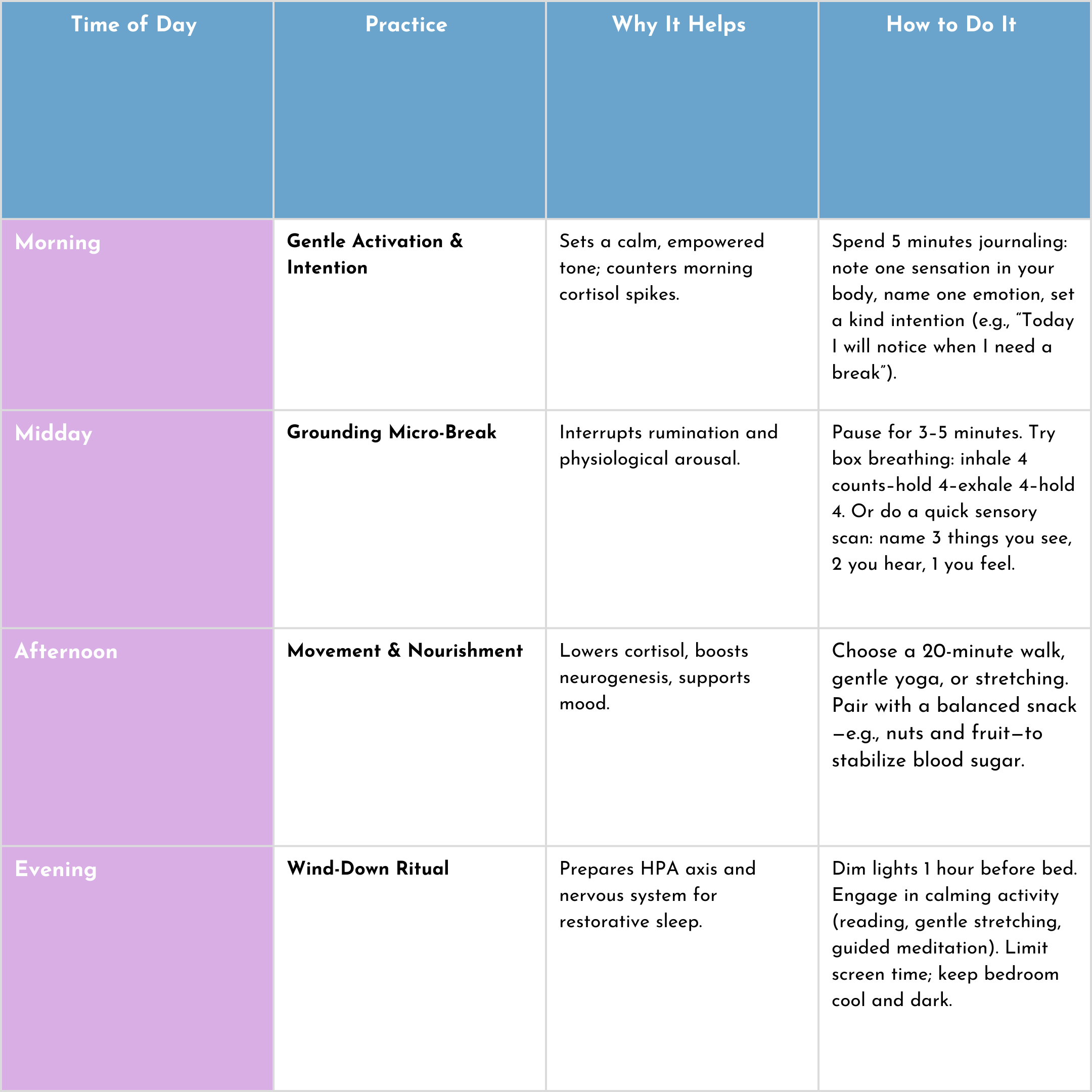

Daily Self-Help Guide: Lifestyle & Trauma-Informed Routine

Trauma reactions are amplified by chronic stress—so managing everyday stressors is foundational. The following integrated guide blends lifestyle pillars with a structured routine to help you rebuild safety, balance your nervous system, and cultivate resilience.

Additional Lifestyle Pillars

Nutrition: Emphasize anti-inflammatory foods—leafy greens, fatty fish, berries—while reducing caffeine and sugar that can spike cortisol.

Sleep Hygiene: Aim for consistent sleep/wake times. If nightmares or insomnia persist, try a brief pre-sleep body scan or progressive muscle relaxation to ease the transition into sleep.

Social Connection: Schedule regular, low-pressure interactions (a coffee with a friend, a support group). Safe relationships buffer stress and reinforce that you are not alone.

Mind-Body Practices: Integrate trauma-informed yoga or tai chi classes that emphasize choice, agency, and gentle pacing. Over time, these foster interoceptive awareness and recalibrate autonomic balance.

Embrace Non-Linearity & Self-Compassion

Healing from trauma is rarely a straight line. Some days you’ll feel grounded; others, the alarm bells may ring again. Track small wins—perhaps you noticed tension and used box breathing instead of dissociating. Celebrate these moments. Each practice you integrate weakens trauma’s hold, strengthening your capacity for safety, connection, and growth.

By combining targeted therapies with a daily lifestyle blueprint, you empower both brain and body to move from constant vigilance toward genuine resilience—and ultimately, toward thriving beyond trauma.

Conclusion

Trauma imprints itself on both body and mind—hijacking ancient stress circuits, reshaping neural networks, and altering emotions, beliefs, and behaviours. Yet the same brain plasticity that embeds trauma also enables healing. By combining evidence-based therapies, cutting-edge innovations, and daily lifestyle practices, individuals can reclaim safety, rebuild resilience, and even experience growth beyond their pre-trauma baseline.

No matter where you are in your healing journey, understanding the interplay between your physiology and psychology is a powerful first step. Be gentle with yourself, celebrate incremental progress, and remember that help is available—whether through professional support, peer communities, or the resources on this site. Your path to well-being is uniquely yours, and every small move toward healing matters.

References:

Neurobiology of PTSD: From Brain to Mind

Yehuda, R., & LeDoux, J. (2007).

(Seminal paper describing HPA axis dysregulation, amygdala/PFC/hippocampal roles.)

Effects of trauma on the HPA axis and sleep

Sinha, R. (2018).

(Explains cortisol rhythms and impact on sleep and arousal.)

Cortisol dysregulation in PTSD and sleep quality

Van Liempt, S., et al. (2013)

(Shows how evening cortisol disrupts sleep in PTSD.)

Epigenetics and intergenerational transmission of trauma

Yehuda, R., et al. (2016).

(Discusses methylation of stress-response genes in Holocaust survivors and descendants.)

ICD-11 and the distinction between PTSD and C-PTSD

World Health Organization (2019)

(Defines PTSD, Complex PTSD, and Acute Stress Reaction in ICD-11.)

Post-Traumatic Growth: Theoretical foundations and neurobiological basis

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G.

(Foundational PTG model, exploring growth post-trauma.)

Trauma-Focused CBT (NICE Guidelines)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK)

(Official guidance on treating PTSD with TF-CBT.)

EMDR therapy research overview

Shapiro, F. (2017). EMDR Institute

(Explains EMDR protocol and science behind it.)

Somatic Experiencing and trauma resolution

Levine, P. A. (2020).

(Overview of how somatic therapy works with nervous system responses.)

MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD: Phase 3 results

Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), 2021

(Details FDA trials showing efficacy of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy.)

Noninvasive brain stimulation in trauma

Philip, N. S., et al. (2018).

(Reviews the use of TMS/tDCS in emotional regulation and PTSD treatment.)

Lifestyle interventions for PTSD and stress-related disorders

Caldwell, K., et al. (2019).

(Supports mindfulness, yoga, exercise, and sleep hygiene for trauma recovery.)

Nutritional psychiatry and trauma recovery

Jacka, F. N., et al. (2017).

(Details anti-inflammatory nutrition’s role in supporting mental health.)

Daily routines and trauma-informed self-care

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)

(Useful guidelines for building safety and predictability in daily life.)

Recommended Reading

The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel van der Kolk

This book explores how trauma reshapes both body and brain, compromising sufferers’ capacities for pleasure, engagement, self-control, and trust.

Amazon UK

Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma by Peter A. Levine

Levine presents a new and hopeful vision of trauma, offering a fresh and optimistic perspective on its treatment.

Amazon UK

Overcoming Trauma and PTSD by Sheela Raja

This workbook integrates skills from ACT, DBT, and CBT to help readers overcome trauma and PTSD.

Amazon UK